Warren Ifergane, CEO, ICG10 Capital, LLC

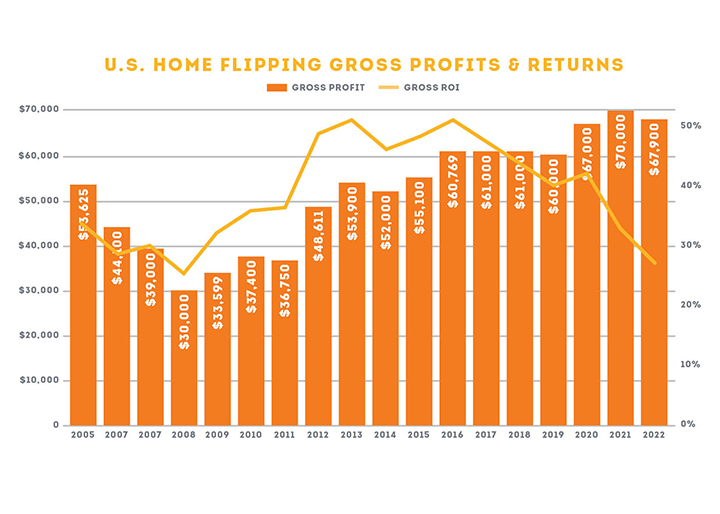

A Conversation About the Economy, Lending and the Real Estate Industry Warren Ifergane is the CEO of ICG10 Capital LLC, a private lending company focusing on financing for fix-and-flips, new construction, and long-term rental properties. Currently lending in 44 states, they are very active in secondary cities such as Jacksonville, FL, Kansas City, MO, and Atlanta, GA. With headquarters in Miami, FL, ICG10 funded $250MM in loans in 2022. REI

Read More